piggy888

การเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์ piggy888 เป็นหนึ่งในกิจกรรมที่ได้รับความนิยมอย่างมากในปัจจุบัน pigspin 888 และเว็บไซต์ที่มีเกมสล็อตให้ทดลองเล่นนั้นไม่เพียงแต่ให้ความสนุกสนานและความบันเทิงเท่านั้น แต่ยังเปิดโอกาส สล็อต pigspin ให้ผู้เล่นทุกคนได้สัมผัสประสบการณ์การเล่นเกมสล็อตที่ดีที่สุด โดยเฉพาะเมื่อมีการรวมค่ายเกมชั้นนำไว้มากมายและสามารถเล่นได้จากทุกที่ทุกเวลา เว็บทดลองเล่นสล็อตที่มีคุณภาพนั้นไม่เพียงแต่มีเกมสล็อตที่น่าสนใจและแตกง่ายเท่านั้น แต่ยังได้รับลิขสิทธิ์ถูกต้องจากค่ายเกมต่าง ๆ ทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถมั่นใจได้ว่าจะได้รับประสบการณ์ที่ปลอดภัยและโปร่งใสในการเล่นอีกด้วย

เว็บทดลองเล่นสล็อตที่ดีที่สุด piggy88 ในปัจจุบันสามารถมอบประสบการณ์การเล่นที่ไม่เหมือนใครให้แก่ผู้เล่นทุกคน ด้วยเกมสล็อตที่มีความหลากหลายและได้รับความนิยมจากผู้เล่นมากมาย โดยแต่ละเกมนั้นมีเอกลักษณ์ที่แตกต่างกัน ไม่ว่าจะเป็นในเรื่องของธีมของเกม pg888 สล็อต รูปแบบการเล่น และคุณสมบัติพิเศษที่เพิ่มความตื่นเต้นให้กับผู้เล่น ไม่ว่าจะเป็นฟีเจอร์โบนัส ฟรีสปิน หรือการคูณรางวัลที่สูงสุด การเล่นเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ในเว็บที่ดีที่สุดนั้นไม่เพียงแต่ช่วยให้ผู้เล่นสนุกสนาน แต่ยังสามารถสร้างกำไรได้อย่างต่อเนื่อง หากคุณเลือกเว็บไซต์ที่มีความมั่นคงและมีระบบการเงินที่เชื่อถือได้

หัวข้อที่น่าสนใจของเว็บไซต์เรา สนใจตรงไหน คลิกเลย !

piggy888 pigspin 888 เล่นเกมที่คุณชื่นชอบได้ทันที!

หนึ่งในจุดเด่นของเว็บไซต์ที่นำเสนอการทดลองเล่นสล็อตนั้น piggy888 pigspin 888 คือ การให้ผู้เล่นได้สัมผัสกับเกมสล็อตที่มีอัตราการจ่ายเงินรางวัล (RTP) สูง ซึ่งมีผลโดยตรงกับโอกาสในการทำกำไรของผู้เล่น สล็อตทดลองเล่นที่มี RTP สูงถึง 98% นั้นมั่นใจได้ว่า ผู้เล่นจะมีโอกาสได้รับรางวัลอย่างแน่นอน โดยไม่ต้องกังวลเกี่ยวกับการถูกโกงหรือการล็อคยูส ในปัจจุบันเกมสล็อตที่มีคุณสมบัติแตกง่ายและให้ผลตอบแทนสูงเป็นที่ต้องการของผู้เล่นอย่างมาก การเลือกเว็บไซต์ที่มีคุณภาพจึงเป็นสิ่งสำคัญที่ทำให้คุณสามารถทำกำไรได้ทุกวัน

นอกจากนี้ การทดลองเล่นสล็อตนั้นเป็นอีกหนึ่งช่องทางที่ทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถฝึกฝนเทคนิคการเล่นสล็อตได้ก่อนที่จะแทงเงินจริง การทดลองเล่นฟรีนั้นไม่มีข้อจำกัดเรื่องเงินลงทุน คุณสามารถเล่นได้ทุกเกมที่คุณต้องการ และค้นหาความรู้สึกของเกมที่เหมาะสมกับคุณ โดยไม่ต้องเสี่ยงเงินทุนของตัวเอง และเมื่อคุณมั่นใจในเกมที่เลือกแล้ว ก็สามารถเปลี่ยนไปเล่นแบบเงินจริงได้ การมีโอกาสทดลองเล่นเกมสล็อตจึงเป็นเรื่องที่น่าตื่นเต้นและเป็นทางเลือกที่ดีสำหรับผู้เล่นมือใหม่และผู้เล่นที่ต้องการเพิ่มทักษะในการเล่น

อีกทั้งการเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์ยังมีข้อดีในเรื่องของโปรโมชั่นและโบนัสที่ช่วยเพิ่มโอกาสในการทำกำไร เช่น การแจกเครดิตฟรีสำหรับสมาชิกใหม่ หรือการแจกฟรีสปินเมื่อเข้าร่วมกิจกรรมต่าง ๆ การรับโบนัสต่าง ๆ นี้จะช่วยเพิ่มโอกาสให้ผู้เล่นสามารถหมุนวงล้อได้มากขึ้น โดยไม่ต้องใช้เงินทุนของตัวเอง นอกจากนี้ การเข้าร่วมกิจกรรมหรือโปรโมชั่นในช่วงเวลาพิเศษ เช่น การหมุนวงล้อรับรางวัล หรือกิจกรรมต่าง ๆ ที่จัดขึ้นภายในเว็บไซต์ ก็เป็นทางเลือกที่ดีในการเพิ่มโอกาสชนะรางวัลใหญ่จากการเล่นสล็อต

piggy888 สล็อต pigspin ระบบเกมที่ทันสมัยที่สุด

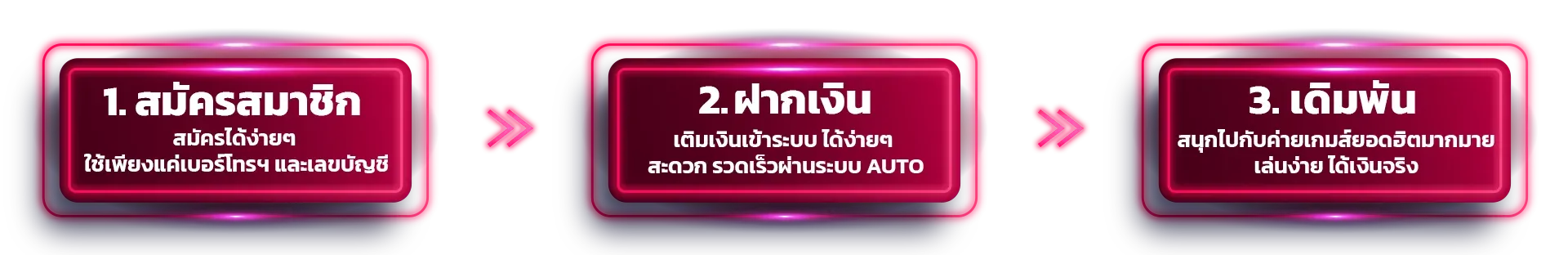

การเล่นสล็อต piggy888 สล็อต pigspin ในเว็บตรงที่ไม่ผ่านเอเย่นต์นั้นเป็นอีกหนึ่งปัจจัยสำคัญที่ทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถมั่นใจได้ว่า ทุกการเล่นนั้นปลอดภัยและได้รับการดูแลที่ดีที่สุด เว็บตรงที่ได้รับการตรวจสอบและมีใบอนุญาตจากหน่วยงานที่เชื่อถือได้นั้นจะมีระบบการเงินที่มั่นคงและการบริการที่รวดเร็ว รวมถึงการฝากถอนที่สะดวกและปลอดภัย การฝาก-ถอนเงินผ่านระบบอัตโนมัติที่สามารถทำได้ภายใน 30 วินาทีนั้นทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถเล่นได้ต่อเนื่อง โดยไม่ต้องรอนาน และไม่ต้องผ่านขั้นตอนที่ซับซ้อน นอกจากนี้การฝาก-ถอนผ่านระบบ True Wallet ก็ทำให้การทำธุรกรรมของคุณสะดวกและรวดเร็วอีกด้วย

การที่เกมสล็อตออนไลน์ในเว็บไซต์ที่ดีที่สุดมีการพัฒนาอย่างต่อเนื่องโดยทีมงานมืออาชีพนั้นหมายความว่า เกมสล็อตที่เปิดให้บริการนั้นจะมีความทันสมัยและมีคุณภาพสูงอยู่เสมอ นอกจากนี้ยังมีการอัปเดตเกมใหม่ ๆ มาให้ผู้เล่นได้ลองเล่นอยู่ตลอดเวลา ทำให้ผู้เล่นไม่เบื่อหน่ายกับการเล่นเกมสล็อตเดิม ๆ และยังสามารถค้นพบเกมใหม่ ๆ ที่อาจจะเป็นเกมที่ทำกำไรให้คุณได้มากกว่าเดิมอีกด้วย การที่เกมมีความหลากหลายและมีฟีเจอร์ใหม่ ๆ จึงเป็นสิ่งที่ดึงดูดผู้เล่นให้เข้ามาลองเล่นมากยิ่งขึ้น

สำหรับผู้เล่นที่ต้องการลุ้นรางวัลใหญ่ การเลือกเล่นเกมสล็อตในเว็บตรงที่ไม่ผ่านเอเย่นต์ยังมีข้อดีในเรื่องของการให้บริการที่รวดเร็วและโปร่งใส เนื่องจากเว็บตรงจะมีการจัดการที่มีความมั่นคงและมีการตรวจสอบจากหน่วยงานที่เกี่ยวข้อง ดังนั้น ผู้เล่นสามารถมั่นใจได้ว่า การเล่นเกมสล็อตในเว็บตรงจะได้รับการดูแลอย่างดีและไม่มีการโกงหรือการล็อคยูสเกิดขึ้น ในการเลือกเว็บเล่นสล็อตจึงต้องคำนึงถึงความมั่นคงและความปลอดภัยของเว็บไซต์เป็นอันดับแรก

สนุกกับเกมสล็อตธีมต่างๆ กราฟิกสวย ระบบโบนัสแตกง่าย

เกมสล็อตออนไลน์ piggy888 ในปัจจุบันยังมีระบบโบนัสและโปรโมชั่นที่ช่วยเพิ่มโอกาสในการทำกำไรให้แก่ผู้เล่น ซึ่งบางเว็บมีการแจกเครดิตฟรีให้แก่ผู้เล่นใหม่ และมีโปรโมชั่นพิเศษสำหรับผู้เล่นที่เป็นสมาชิกอยู่แล้ว เช่น การแจกฟรีสปิน การเพิ่มเงินเดิมพัน หรือการคูณเงินรางวัล เมื่อคุณเข้าเล่นในเวลาที่เหมาะสมหรือเมื่อมีโปรโมชั่นพิเศษ นอกจากนี้การรับโบนัสในรูปแบบต่าง ๆ จะช่วยให้คุณมีโอกาสเล่นเกมได้มากขึ้น และมีโอกาสชนะรางวัลใหญ่ได้สูงขึ้น

ไม่เพียงแต่การเล่นที่สนุกสนานและตื่นเต้นเท่านั้น evolution การเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์ยังสามารถเป็นช่องทางในการสร้างรายได้ที่ดีให้กับคุณอีกด้วย ด้วยอัตราการจ่ายที่สูงและโอกาสในการชนะรางวัลใหญ่ที่มีมากมาย ผู้เล่นหลายคนจึงเลือกที่จะใช้เกมสล็อตเป็นช่องทางในการทำกำไรอย่างจริงจัง ดังนั้นหากคุณยังไม่เคยทดลองเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์มาก่อน อย่ารอช้า ลองเข้าไปทดลองเล่นและสัมผัสประสบการณ์ใหม่ ๆ ที่จะทำให้คุณตื่นเต้นไปกับการลุ้นรางวัลใหญ่ทุกครั้งที่หมุนวงล้อ

สุดท้ายนี้ การเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์ในเว็บไซต์ที่มีคุณภาพไม่เพียงแต่ทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถสนุกสนานและตื่นเต้นไปกับเกม แต่ยังเป็นช่องทางที่ดีในการทำกำไรจากการเล่นเกมออนไลน์ ที่สำคัญคือทุกคนสามารถเข้ามาลองเล่นได้อย่างง่ายดาย ไม่ว่าจะเป็นมือใหม่หรือผู้ที่มีประสบการณ์ในการเล่นมาก่อน เว็บไซต์ที่ให้บริการเกมสล็อตออนไลน์มักจะมีการแนะนำเทคนิคและเคล็ดลับการเล่นที่ช่วยให้ผู้เล่นสามารถเพิ่มโอกาสในการชนะรางวัลใหญ่ได้ ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการเลือกเกมที่มี RTP สูง การเลือกช่วงเวลาในการเล่นที่เหมาะสม หรือการใช้ฟีเจอร์ต่าง ๆ ของเกมให้เกิดประโยชน์สูงสุด

piggy888 piggy88 เว็บตรงไม่ผ่านเอเย่นต์

การเลือกเล่นเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ piggy888 piggy88 จากเว็บที่มีคุณภาพนั้นยังมีข้อดีอื่น ๆ ที่คุณไม่ควรพลาด เช่น ระบบรักษาความปลอดภัยที่ทันสมัยและการบริการลูกค้าที่มีคุณภาพ ซึ่งสามารถตอบสนองความต้องการของผู้เล่นได้อย่างครบถ้วน ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการแนะนำเกมใหม่ ๆ หรือการช่วยเหลือในกรณีที่เกิดปัญหาต่าง ๆ

รวมถึงการดูแลสมาชิกให้สามารถเล่นเกมสล็อตได้อย่างสนุกสนานและมั่นใจ นอกจากนี้ยังมีระบบที่รองรับการเล่นผ่านมือถือ ทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถเข้าเล่นเกมได้ทุกที่ทุกเวลา ไม่ว่าคุณจะเป็นผู้เล่นมือใหม่หรือมือโปร หากคุณเลือกเล่นกับเว็บที่มีคุณภาพและปลอดภัย

คุณก็สามารถสนุกสนานไปกับการเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์ได้อย่างเต็มที่ ลุ้นรางวัลใหญ่ได้ทุกวัน พร้อมทั้งได้รับการบริการที่ดีเยี่ยมและระบบการเงินที่มั่นคง สิ่งเหล่านี้คือเหตุผลที่ทำให้การเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์กลายเป็นหนึ่งในกิจกรรมที่ได้รับความนิยมอย่างมากในปัจจุบันและหากคุณยังลังเลอยู่ ลองเข้ามาสัมผัสประสบการณ์การเล่นที่ไม่มีวันเบื่อและโอกาสในการทำกำไรที่ไม่สิ้นสุด

piggy888 pg888 สล็อต เล่นง่าย ถอนได้จริง

การเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์ piggy888 pg888 สล็อต ในปัจจุบันได้กลายเป็นกิจกรรมยอดนิยมที่นักพนันหลายคนหันมาสนใจ เนื่องจากไม่เพียงแต่ให้ความสนุกและความตื่นเต้นที่ไม่มีที่สิ้นสุด แต่ยังมีโอกาสที่จะได้รางวัลใหญ่จากการเล่นเกมได้ทุกที่ทุกเวลา สิ่งที่ทำให้การเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์เป็นที่นิยมอย่างมากนั้นคือ ความสะดวกสบายและความหลากหลายของเกมที่มีให้เลือกเล่นอย่างหลากหลาย ทุกค่ายเกมที่ร่วมอยู่ในเว็บไซต์นั้นได้รับการออกแบบมาเพื่อให้ผู้เล่นได้รับประสบการณ์ที่ดีที่สุด ทั้งในแง่ของกราฟิกที่สวยงาม ฟีเจอร์ที่น่าสนใจ และรางวัลใหญ่ที่รอคุณอยู่ทุกครั้งที่หมุนวงล้อ

เว็บไซต์ที่ให้บริการทดลองเล่นสล็อตนั้นเป็นหนึ่งในทางเลือกที่ดีที่สุดสำหรับผู้เล่นที่ต้องการทดสอบเกมต่าง ๆ โดยไม่ต้องเสี่ยงใช้เงินจริง การที่ผู้เล่นสามารถทดลองเล่นเกมสล็อตได้ฟรีนั้น เป็นสิ่งที่ช่วยให้คุณได้ค้นพบเกมที่ตรงกับความชอบและความสามารถของตัวเอง โดยที่ไม่ต้องกังวลว่าจะสูญเสียเงินทุนไปโดยเปล่าประโยชน์ คุณสามารถลองเล่นทุกเกมที่มีอยู่ในเว็บไซต์เหล่านี้และศึกษากลไกต่าง ๆ ของเกม รวมถึงฟีเจอร์พิเศษที่แต่ละเกมมี ซึ่งสิ่งนี้สามารถช่วยเพิ่มโอกาสในการชนะรางวัลใหญ่ในภายหลังได้

อีกทั้งการเล่นสล็อตออนไลน์ในเว็บที่มีระบบการเงินที่มั่นคงและปลอดภัยยังช่วยเพิ่มความมั่นใจให้กับผู้เล่น ไม่ว่าจะเป็นการฝากเงินหรือถอนเงิน ผู้เล่นสามารถทำได้อย่างรวดเร็วผ่านระบบอัตโนมัติที่ไม่ต้องรอนาน การที่มีระบบฝาก-ถอนที่รวดเร็วภายใน 30 วินาที ถือเป็นอีกหนึ่งข้อดีที่ทำให้ผู้เล่นรู้สึกสะดวกสบายและไม่ต้องเสียเวลาไปกับขั้นตอนที่ซับซ้อน ซึ่งช่วยให้สามารถเล่นเกมได้อย่างต่อเนื่องโดยไม่หยุดชะงัก นอกจากนี้ ระบบการฝาก-ถอนที่รองรับผ่าน True Wallet ก็เป็นทางเลือกที่สะดวกและรวดเร็ว ทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถฝากและถอนเงินได้ตามต้องการในเวลาอันรวดเร็ว

สล็อตเว็บตรงไม่มีขั้นต่ำ ทุนน้อยก็รวยได้

เกมที่มีการอัปเดตใหม่ ๆ อยู่เสมอนั้นเป็นอีกหนึ่งปัจจัยที่ทำให้ผู้เล่นไม่รู้สึกเบื่อหน่าย สล็อต ซื้อ ฟรี ส ปิ น ทดลองเล่น โดยเกมสล็อตในปัจจุบันมักจะมีฟีเจอร์พิเศษและรูปแบบการเล่นที่น่าสนใจ อาทิเช่น ฟีเจอร์ฟรีสปินที่ช่วยให้ผู้เล่นมีโอกาสหมุนวงล้อฟรี และการคูณเงินรางวัลที่เพิ่มขึ้นเมื่อได้สัญลักษณ์พิเศษต่าง ๆ การเล่นเกมสล็อตที่มีฟีเจอร์เหล่านี้จะเพิ่มความสนุกและความตื่นเต้นให้กับผู้เล่นได้มากขึ้น ทั้งยังมีโอกาสได้รับรางวัลใหญ่จากฟีเจอร์เหล่านี้อีกด้วย

ยิ่งไปกว่านั้น ความหลากหลายของเกมสล็อตที่มีในเว็บไซต์ทดลองเล่นสล็อตยังเป็นสิ่งที่ดึงดูดผู้เล่นอย่างมาก จากเกมสล็อตคลาสสิกที่มีรูปแบบการเล่นที่เข้าใจง่าย ไปจนถึงเกมสล็อตที่มีฟีเจอร์พิเศษสุดตระการตาที่มาพร้อมกับกราฟิกที่น่าตื่นตาตื่นใจ รวมถึงธีมเกมที่มีความหลากหลาย เช่น ธีมแฟนตาซี ธีมประวัติศาสตร์ หรือแม้กระทั่งธีมจากภาพยนตร์หรือการ์ตูนที่ได้รับความนิยม ทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถเลือกเล่นเกมที่ตรงกับความชอบและรสนิยมของตัวเองได้อย่างหลากหลาย

เกมสล็อตออนไลน์ที่แตกง่ายและมีอัตราการจ่ายเงินรางวัลที่สูงนั้นถือเป็นจุดขายที่สำคัญของเว็บไซต์เหล่านี้ โดยเฉพาะเกมสล็อตที่มีอัตราการจ่าย RTP สูงถึง 98% ซึ่งถือว่าเป็นระดับที่สูงมากเมื่อเทียบกับเกมสล็อตในเว็บอื่น ๆ เมื่อเกมสล็อตมี RTP ที่สูง โอกาสในการชนะรางวัลใหญ่จึงมีมากขึ้น ทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถมั่นใจได้ว่า ทุกครั้งที่คุณหมุนวงล้อมีโอกาสที่จะได้รับรางวัลกลับมาทุกครั้ง และที่สำคัญการเล่นสล็อตที่มีอัตราการจ่ายสูงนี้ยังทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถทำกำไรจากการเล่นได้ทุกวัน

คำถามที่พบบ่อย (FAQ)

การฝาก-ถอนเงินใน Piggy888 ทำได้อย่างไร ?

การฝาก-ถอนเงินเป็นกระบวนการที่สะดวกและรวดเร็ว ด้วยระบบฝาก-ถอนอัตโนมัติที่รองรับการทำธุรกรรมผ่านหลายช่องทาง มารวยไปด้วยกัน เช่น ผ่านธนาคารชั้นนำและ True Wallet โดยสามารถทำการฝากเงินได้ทันทีภายใน 30 วินาที และถอนเงินได้รวดเร็วไม่เกิน 1 นาที ผู้เล่นสามารถฝากเงินเริ่มต้นเพียงแค่ 1 บาทก็สามารถเล่นเกมได้ และที่สำคัญระบบการเงินมีความปลอดภัยสูง ใช้ระบบเข้ารหัสข้อมูลที่ทันสมัยเพื่อปกป้องข้อมูลส่วนบุคคลของผู้เล่น การถอนเงินก็ทำได้ง่ายดาย โดยไม่มีค่าธรรมเนียมเพิ่มเติม ทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถถอนเงินได้เต็มจำนวนที่ชนะจากการเล่นเกมสล็อตได้ทุกครั้ง

เกมที่มีใน Piggy 888 มีอะไรบ้าง ?

นำเสนอเกมสล็อตที่หลากหลายมากมายจากค่ายเกมชั้นนำทั่วโลก ซึ่งรวมถึงเกมสล็อตคลาสสิกที่มีรูปแบบการเล่นแบบดั้งเดิมจนถึงเกมสล็อตที่มีฟีเจอร์ทันสมัย เช่น วงล้อแบบ 3 มิติ หรือเกมสล็อตที่มีเนื้อเรื่องและกราฟิกที่น่าตื่นตาตื่นใจ ที่สำคัญเกมสล็อตมักจะมีโบนัสพิเศษ เช่น ฟรีสปิน ตัวคูณรางวัล และฟีเจอร์อื่น ๆ ที่เพิ่มความสนุกและโอกาสในการชนะรางวัลใหญ่ นอกจากนี้ยังมีการอัพเดทเกมใหม่ ๆ อย่างสม่ำเสมอเพื่อให้ผู้เล่นได้สัมผัสประสบการณ์การเล่นที่ไม่ซ้ำซาก นอกจากนี้ยังมีเกมที่รองรับผู้เล่นทุกระดับ ทั้งผู้เล่นที่มีทุนน้อยและผู้เล่นที่ต้องการลุ้นรางวัลใหญ่ ทุกคนสามารถเพลิดเพลินไปกับเกมได้อย่างไม่จำกัด